A powerful year for Truth and Treaty

In 2024 the Yoorrook Justice Commission investigated the systemic injustices faced by First Peoples in land, sky and waters, education, health, and housing. From hearing evidence at the site of the first recorded massacre in Victoria to the premier’s historic visit to Coranderrk, it has been a year filled with powerful moments.

2024 has been a remarkable year in Victoria’s story. This was illustrated by two major milestones which occurred in a single week.

The 19th of November marked 190 years since Edward Henty’s landing on Gunditjmara Country in 1834.

This was the beginning of colonisation in Victoria and the start of an unbroken line of injustice faced by First Peoples which continues to this day. The anniversary was a sad occasion for many Traditional Owners and a time of reflection and remembrance.

Just two days later saw the formal beginning of statewide Treaty negotiations between the First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria and the Victorian Government.

This incredible ceremonial gathering of Traditional Owners set the bar for a new beginning in the relationship between First Peoples and all Victorians. It also celebrated the ongoing strength and resistance of First Peoples and their continued connection to culture, community and Country.

Elders, Aboriginal leaders and community members gathered alongside representatives of government including Premier Jacinta Allan to commemorate the historic moment, which had been decades in the making.

It was another major step on the path towards a better shared future; a future in which First Peoples thrive, and everyone benefits.

Yet across 2024, the Yoorrook Justice Commission has witnessed so many other historic moments, during its inquiries into the systemic injustices facing First Peoples in relation to land, sky and waters, education, health, housing and the economy.

Many of the recommendations made by Yoorrook will be the subject of Treaty negotiations. These two processes are closely connected.

In March, Yoorrook opened its public hearings into land on Gunditjmara Country under the watchful eye of Budj Bim.

The volcano erupted around 30,000 years ago. Its lava – the Tyrendarra flow – snaked its way south to the sea, creating the rocky terrain Gunditjmara people used to develop the oldest aquaculture system in the world.

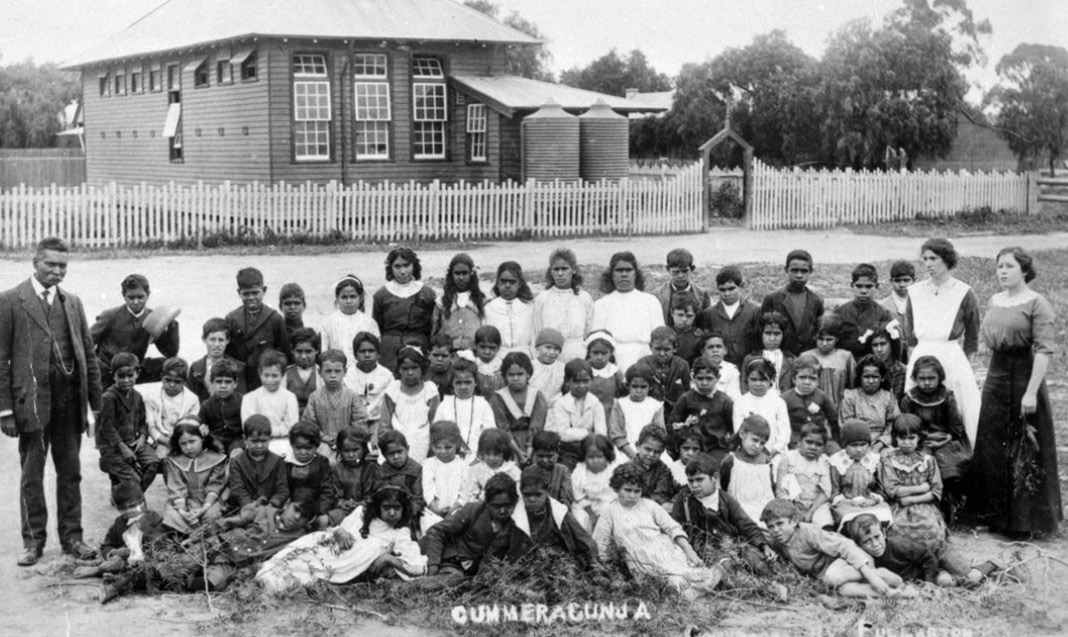

Yoorrook heard that it was here, near the end of the flow, where the first recorded massacre of First Peoples took place over a whale carcass around 1833.

The following year Edward Henty arrived, establishing the first permanent European settlement at Portland, beginning what was described to the Commission as the “swiftest expansion within the British empire of any occupation of land”.

Yoorrook heard that from the time of first European contact and the 1850s, the population of First Peoples in Victoria plummeted from around 60,000 to less than 2,000, owing largely to foreign diseases and bloody violence.

Professor Marcia Langton described the 49 recorded massacres as “the tip of the iceberg”.

In April, Premier Jacinta Allan visited the former Coranderrk Aboriginal Mission near Healesville, sitting with Wurundjeri Traditional Owners and Commissioners while surrounded by towering manna gums. A few days later the Premier gave evidence to Yoorrook, admitting she felt “a sense of shame and distress” that she did not know about the massacres which took place close to where she lives.

In May and June, Yoorrook held social justice hearings. The Commission heard how racism and discrimination had infiltrated and embedded itself within the education, health and housing systems.

Dozens of First Peoples gave evidence, sharing personal stories of strength and injustice, detailing the ongoing harm caused by systems which were not designed by or for Aboriginal people.

Elias Jarvis talked about the “incessant gaslighting of low expectations” experienced by Aboriginal students, while Aunty Jill Gallagher revealed how healthcare in prisons was getting worse for First Peoples, not better.

Darren Smith from Aboriginal Housing Victoria said if the rate of Aboriginal people accessing homelessness services (17 per cent) was applied across the entire population, “there would be 1 million people accessing homelessness services in Victoria every year. It would be an absolute crisis.”

The word “crisis” was also used repeatedly by government ministers.

Housing Minister Harriett Shing acknowledged the housing crisis facing First Peoples, describing it as an “abject failure” by government. “We created Aboriginal homelessness and then we turned away from it. And for too long we refused to even acknowledge that its existence and impact was our doing,” she said.

Health Minister Mary-Anne Thomas accepted that Victoria’s health services were not culturally safe places for First Peoples, and that racism in hospitals was at “crisis” point.

Education Minister Ben Carroll acknowledged the “historical failings” of the state’s education system which has “played a significant role in reinforcing racist perceptions and stereotypes about First Peoples and perpetuate false narratives about cultural history”.

Following the powerful evidence of Suzannah Henty – a descendant of coloniser James Henty – Yoorrook saw an increasing number of non-Indigenous Victorians come forward to make a submission or provide testimony in public hearings.

In September, three non-Indigenous witnesses gave evidence during the Descendants Day hearing, providing new perspectives on key moments in Victoria’s shared history while reflecting on the actions of their relatives.

Among them was Peter Sharp, a great grandson of former Prime Minister Alfred Deakin.

Sharp talked about Deakin’s role in the passing of the 1886 Amendment to the Aboriginal Protection Act, more commonly known as the Half-Caste Act.

The legislation had a devastating impact on Victoria’s First Peoples and played a key role in the beginning of the Stolen Generations.

In November, Yoorrook’s submissions process closed. In all, more than 1,000 submissions were made to the Commission, from individuals, families, councils, universities, academics, Aboriginal-led organisations and many others.

This builds on Yoorrook’s enormous evidence base, which includes 67 public hearing days with 229 witnesses, hundreds of community information sessions, roundtable discussions, prison visits and visits to sites of historical and cultural significance, as well as more than 10,000 documents provided in response to Requests for Information or Notices to Produce.

With Yoorrook due to wind up operations on 30 June 2025, the coming months will be busy delivering recommendations, writing the final report and the official public record, and continuing our work to build a shared understanding of Victoria’s full story.

Because when we all understand the truth of the past, and how this impacts the present, we can forge a better future together.

It is full steam ahead on that journey towards a better shared future. History will be the ultimate judge of how successful we are. Regardless, 2024 was a remarkable year.