Descendants hearing shows all Victorians have a part to play

During Yoorrook’s Descendants Day hearing, the Commission heard powerful evidence from three non-Indigenous witnesses, including descendants of early colonial figures. They talked about the theft of Aboriginal land, massacres, and the Aborigines Protection Act of 1886, more commonly known as the ‘Half Caste’ Act.

On September 4, 2024, the Yoorrook Justice Commission held a Descendants Day hearing with three non-Indigenous witnesses. Together they helped shed light on the “hidden truth” of the colonisation of Victoria. Commissioners heard from Katrina Kell, Peter Sharp and Elizabeth Balderstone.

Scroll down or click a heading below to learn more.

- Katrina Kell – researcher, author and fourth-generation matrilineal descendant of Captain James Liddell, who brought Edward Henty to Gunditjmara Country in November 1834 on board ‘the Thistle’, leading to the first permanent European settlement in what would become the State of Victoria.

- Peter Sharp – a great grandson of former Prime Minister Alfred Deakin, who has researched Deakin’s involvement in the passage of the Aborigines Protection Act 1886, more commonly known as the ‘Half Caste’ Act.

- Elizabeth Balderstone – the current owner of a property in Gippsland on which the ‘Warrigal Creek’ massacre occurred in 1843.

Katrina Kell

When Katrina Kell was young, her grandmother told stories of their “illustrious” ancestor Captain James Liddell.

Liddell captained the ship that sailed Edward Henty to establish the first permanent European settlement on Gunditjmara Country in 1834.

Many of Kell’s family members born at the time were even given “Henty” as a middle name, in recognition of the Henty brothers.

But as an adult, using her skills as a researcher, Kell began to discover what she called the “inherited shame” of Captain Liddell’s legacy.

And it was with a sense of duty to share the true history of Victoria’s colonial past that motivated Kell and two other non-Indigenous witnesses to give evidence to the Yoorrook Justice Commission at the Descendants Day hearing on 4 September 2024.

Kell was joined by Peter Sharp, a great grandson of Alfred Deakin, and Elizabeth Balderstone, the current owner of a property in Gippsland on which the Warrigal Creek massacre of First Peoples occurred in 1843.

The hearing aimed to shed light on the colonisation of Victoria, bringing forward stories and experiences of non-Indigenous people.

Kell’s evidence went back to the beginning of European settlement.

Using available historical records, diary entries and media articles, Kell was able to piece together Captain Liddell’s movements at that time.

She said one of the most distressing discoveries was Captain Liddell’s involvement in the abandonment of Kalloongoo, an Aboriginal woman, who was stolen from her family as a child, enslaved and then sold to sealer and early settler William Dutton.

Kalloongoo was said to have been left at King Island in Bass Strait, and her child taken away from her.

“That’s a horrible story to have discovered, to know that he was involved with that and … obviously carried out the orders to do this,” she said.

In her evidence, Kell also talked about the possibility Captain Liddell may have witnessed or been involved in the Convincing Ground massacre in the early 1830s.

Yoorrook has heard evidence scores of Kilcarer Gunditjmara people were killed in the massacre.

For Kell the hidden truth of her ancestor’s story brings a sense of “inherited shame”.

“We like to take pride in our families, don’t we? And of their achievements. And I think it is an inherited shame because part of the shame is … the fact that we didn’t learn anything about this,” she said.

“We were never told anything about this so there has been this intergenerational denial, not passing down what has happened, what the truth is.”

Kell said she hoped there would be changes to the school curriculum to help non-Indigenous Australians understand the state’s violent past, and face up to it with “honest and critical eyes”.

“While these stories are hidden and not shared, and the truth is denied, how can you call yourself a nation in this day and age?”

And she encouraged all Victorians to engage in truth-telling.

“Accept that there could be things that you will discover that you are not happy about, that you are disappointed to learn that your ancestors have been involved with, but to think about it as a duty of care to First Nations people and to this country and to this nation, and making it an honest nation that you can actually feel proud of.”

Peter Sharp

Peter Sharp’s evidence to Yoorrook was the culmination of five years of extensive private research, which he commenced after being given a copy of Judith Brett’s The Enigmatic Mr Deakin.

The biography connected Deakin with the 1886 Amendment to the Aboriginal Protection Act, commonly known as the Half-Caste Act.

“As soon as I read those paragraphs, I thought ‘this is the Stolen Generations’,” Sharp said in his witness statement.

Sharp’s research included reviewing publicly available material and primary sources, particularly around the passing of the Act.

He described Deakin’s appointment as Chief Secretary of Victoria in March 1886 as “a very significant moment” because it made him responsible for Aboriginal policy.

This gave Deakin “an opportunity to ensure that the number of people recognised as Aboriginal in Victoria could be drastically reduced and then would continue to decline”, Sharp said.

Two weeks after taking office as Chief Secretary, Deakin directed his office to prepare a draft Act.

Sharp said that after tabling the Bill in June 1886, Deakin delayed its second and third readings until the very last item of business for the parliamentary year.

And while the Bill contained “complex and convoluted” language, it was only given to members shortly before Deakin began his speech, which took about two minutes.

“No-one would have expected his speech to be so short,” Sharp said.

“This legislation, which was to have such devastating effects and ongoing consequences which can never be reversed, was passed in under 10 minutes.

“While I’m not an expert on these matters, my view is that this appears to have been a deliberate, well-planned tactic.”

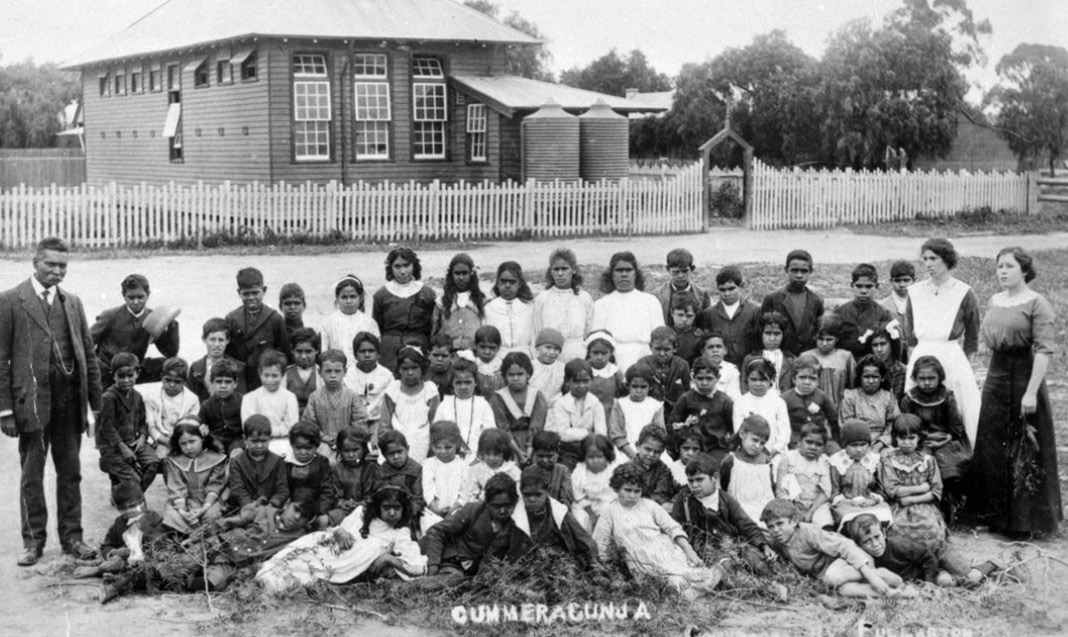

The Bill redefined Aboriginality to exclude people of mixed heritage, forbidding so called ‘half-castes’ from age eight to 34 from remaining on the reserves and receiving support.

This in effect was the beginning of the legal removal of First Peoples children from their families.

“It wasn’t just that they were disallowed to stay on the reserves where their family ties could remain strong and kinship could be preserved, language could be preserved,” Sharp said.

“They were forced to disperse and the policy of removal of children … came into being and … it was the beginning of the Stolen Generations.”

In his evidence to the Commission, Sharp apologised for Deakin’s role in the law.

“To all those viewing who themselves, or whose families have been and still are being impacted by the introduction of laws and policies in which a member of my family played such a significant role, I say that I am personally profoundly sorry.”

Elizabeth Balderstone

Elizabeth Balderstone is the current owner of a farming property in Gippsland, in Victoria’s south-east, on which the Warrigal Creek massacre occurred in 1843.

Balderstone, views herself and her family as the current “custodians” of the land.

“Technically I know we do own the land, the title to the land, which I acknowledge was never ceded … but the term “custodianship” really reflects what I feel in my time being there. I want to be looking after it as well as having the privilege and challenge of farming it,” she said.

Warrigal Creek was one of four massacres in the area in July 1843, according to the University of Newcastle’s massacre mapping project, which Yoorrook has previously heard evidence on.

The mapping project utilises extensive archival sources including newspapers, scholarly articles, private diaries and correspondence.

It found Donald Macalister, the nephew of squatter Lachlan Macalister, was killed by Brataualang Traditional Owners near Port Albert, Gippsland, in early July 1843.

This was a reprisal killing for the regular shooting and killing of Aboriginal people in the area.

When news of Macalister’s death broke, Angus McMillan, who was Lachlan Macalister’s former overseer, formed an avenging party of 20 horsemen, known as ‘The Highland Brigade’.

The group came upon a large group of Brataualung People camped at the waterhole at Warrigal Creek and fired at them, killing an estimated 75 people.

Three further massacres of around 25 Brataualung people each were recorded at sites nearby in the following days, according to the project.

“I have over the years felt a growing awareness of the responsibility and gravity of caring for the massacre site in the gentlest and quietest way possible,” Balderstone said in her submission.

“And simultaneously, I am committed to ensuring that the truth of the massacre is told and understood more widely by Gippslanders initially, and by the Victorian and wider Australian community at large.”

Balderstone, who first called the property home in 1980, wants to see the site of the massacre permanently protected.

She told the Commission she has built strong relationships with local Traditional Owners, particularly Elders, and is guided by them on how to care for the site.

“They have been incredibly important for me to have that chance to connect and break down that bridge that often seems to be between non-Indigenous and Indigenous Australians,” Balderstone said.

Balderstone said she and her family would be “very happy to hand back Traditional Ownership” if requested and has investigated a range of solutions to return the land in some form to First Peoples.

She hopes her testimony will encourage other non-Indigenous Victorians to challenge their own understanding of history.

“I think we have all got a duty to do it, as Victorians and Australians,” Balderstone said.

“To look at where we live. Investigate the story of European colonisation. Think about what it meant for the people that were there and what happened and what’s happened to the landscape and acknowledge that story and then also the benefits so many of us have had because of that tragic beginning to Australia.

“I just hope as a nation we can share those benefits.”

Yoorrook Chair, Professor Eleanor Bourke said the Descendants Day witnesses showed truth-telling isn’t a process only for First Peoples to take part in.

All Victorians have a role to play.

“When we understand what has happened in the past and how this impacts the present, we can create a better future and have a better understanding between all Victorians,” Chair Bouke said.

“We need to have all Victorians come forward and share the burden of this truth-telling, if that’s possible.”