This content may contain images, names or voices of deceased persons and may include outdated or culturally sensitive language, presented for historical accuracy and with respect to First Peoples perspectives.

The story of Coranderrk Station shows the strength and resistance of First Peoples and systemic injustices faced. Follow the story here to listen and learn about our shared history and work towards a shared future together.

Scroll down or click a heading below to learn more.

- Prior to Coranderrk 1859

- How was Coranderrk established?

- Established in 1863

- Triumph To Tragedy

- 1881 Inquiry

- Coranderrk Today

Prior to Coranderrk 1859

In 1859, Uncle Simon Wonga (Wurundjeri Ngurungaeta) helped the Taungurung people secure the Acheron Station for farming.

Wurundjeri people had been experiencing similar setbacks after settlers moved into their encampment at Yering.

They cleared 17 acres of land and planted 7 acres of crops, but despite their efforts and protests, the government forced them to move to unsuitable land for farming at Mohican Station.

How was Coranderrk established?

Wurundjeri and Taungurung families, with befriended settlers John and Mary Green, crossed the Yarra Ranges and settled where the Yarra River meets Badger Creek. They named the site Coranderrk, after the native Christmas Bush in the area.

This land was originally part of 38,000 acres of squatters’ leases taken by the Ryrie brothers and later became part of a 44,000-acre property called “Yarradale,” owned by William Nicholson, former Victorian Premier (1859–1860).

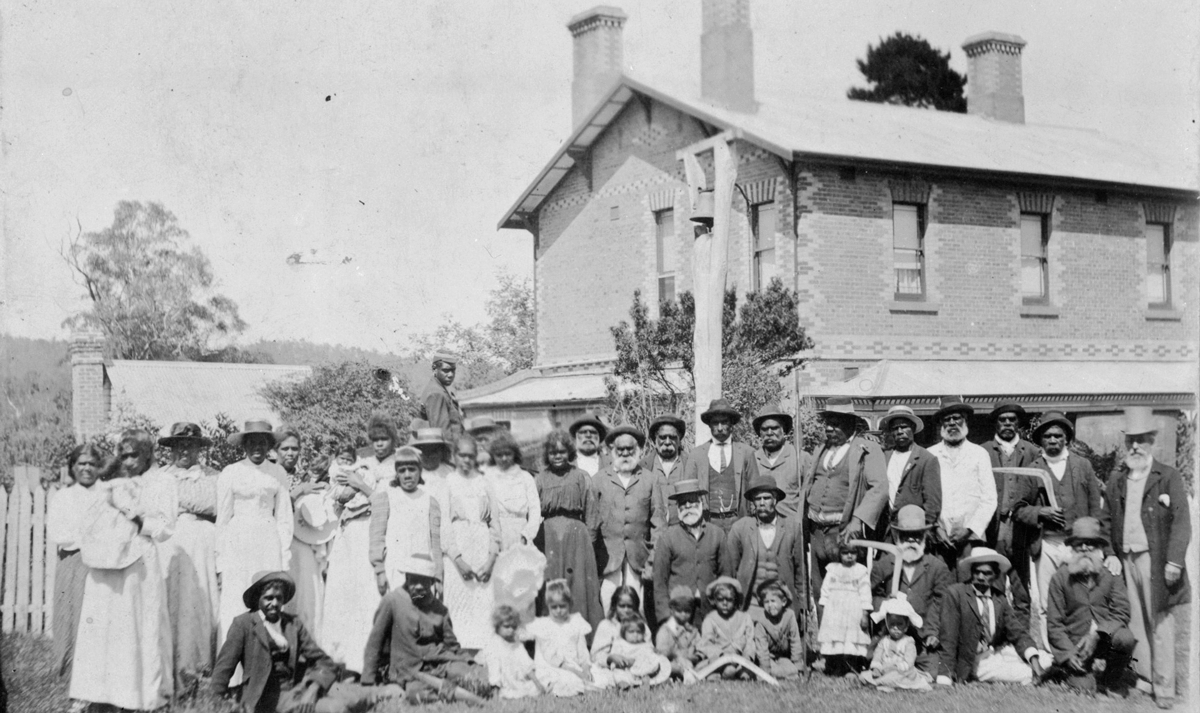

Uncle Wonga led 15 Wurundjeri, Taungurung and Boon Wurrung men to Melbourne to request ownership of their settlement from the Governor. Their efforts succeeded, and in June 1863, 2,300 acres (later expanded to 4,850) were reserved for them.

Established in 1863

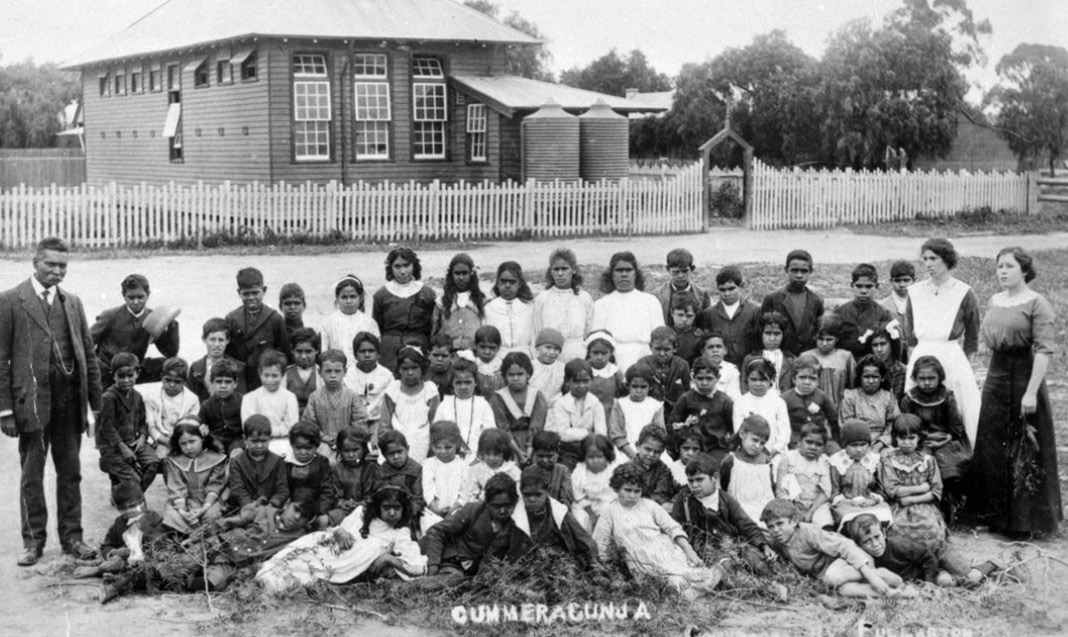

Kulin people. They built a thriving farming community, maintained cultural practices and self-governed through a court assembly, deciding their own rules and conduct.

Coranderrk’s success was a direct result of the Kulin people’s hard work, with settlers like John Green serving as supportive allies.

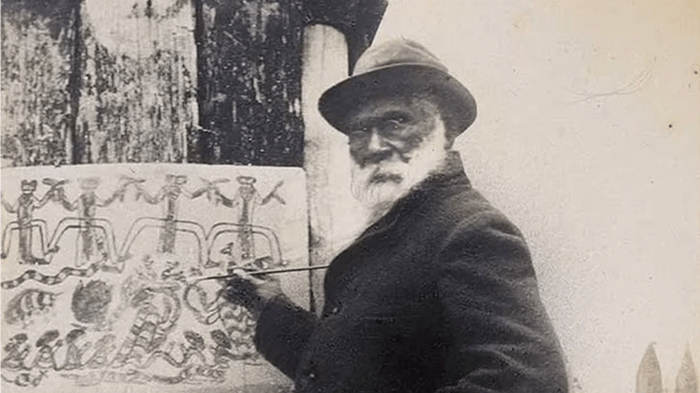

Coranderrk was well on its way to self-sufficiency and to achieve this, John Green experimented with various crops that would provide additional income. He attempted to grow tobacco, but had more success with hops.

By 1874, two kilns for drying hops had been constructed.

Triumph To Tragedy

The success of the hops crops at Coranderrk ultimately contributed to its struggles.

Local squatters, eager to claim the valuable land, pushed for Coranderrk’s closure. The Board began to recognise the profitability of the hops crop and saw it as an opportunity to exploit a controlled workforce.

Disagreements over John Green’s management of the station led to tensions within the Board, with some members actively working to remove him.

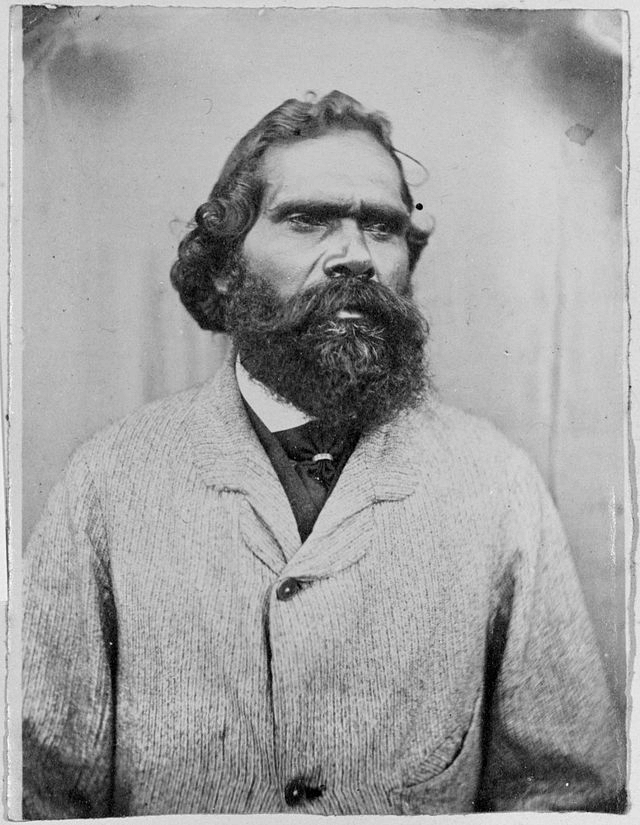

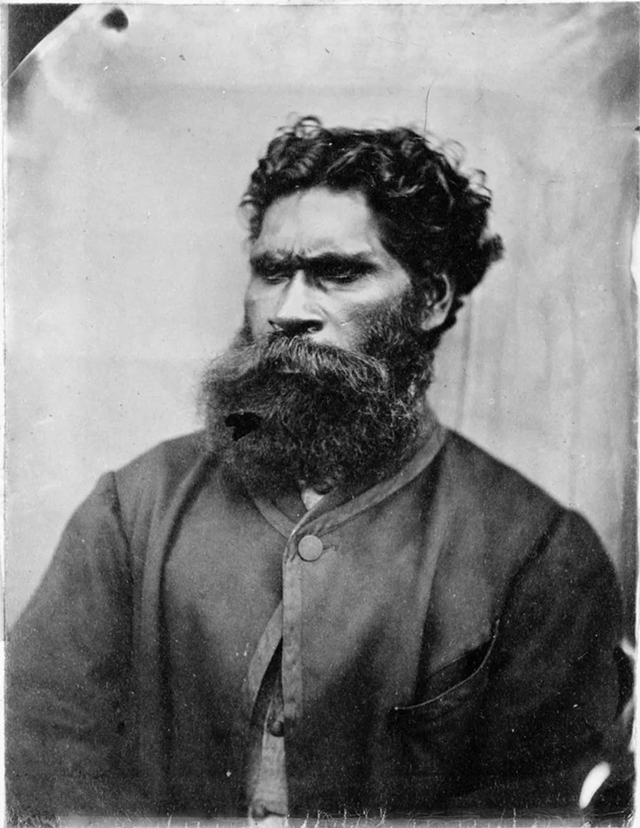

In the mid-1870s, two significant events shook Coranderrk: The death of Simon Wonga and the Board’s forced resignation of Green as superintendent. With Wonga leaving no children, his cousin, William Barak, became the new Ngurungaeta (leader).

As the Board implemented increasingly authoritarian policies and conditions, conditions at Coranderrk worsened.

Those living at Coranderrk began a determined fight for greater autonomy and the reinstatement of Green. Barak, alongside many Coranderrk residents, led a campaign of non-violent resistance and strategic lobbying. They were supported by European allies, including John Green and Anne Bon, a committed advocate for Aboriginal rights and supporter of the Coranderrk people.

During this time, the Board further undermined Coranderrk by cutting its funding and appointing a series of unsuitable managers, which only worsened conditions and mismanagement at the station.

Uncle Barak opposed this through petitions and famously declared:

“Me no leave it, Yarra, my country.”

1881 Inquiry

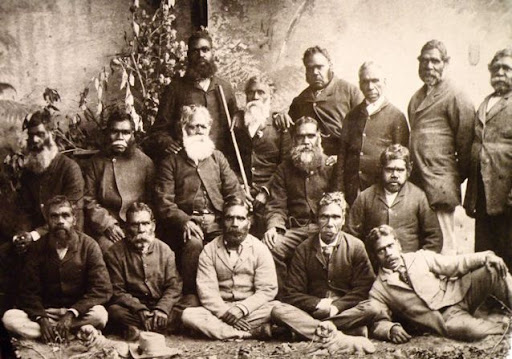

In 1881, Uncle Barak led 22 men on a 60-kilometre walk from Coranderrk to Parliament House to protest threats to the station.

This led to the first Parliamentary Inquiry in Victoria that directly addressed First Peoples demands for self-determination and land.

During the inquiry, 22 Coranderrk residents testified about the harsh conditions they endured, including inadequate housing, lack of medical care, insufficient food, enforced labor in the hops fields and the absence of wages to buy essentials.

John Green was not reinstated as superintendent but remained in Healesville, close to the Coranderrk community.

The challenges continued with the introduction of the so-called 1886 ‘Half-Caste Act’, which forcibly removed all ‘half-caste’ people (those with Aboriginal and European ancestry) aged 15 to 35 from Coranderrk and other missions, breaking up families, dismantling the community and depriving Coranderrk of its young workforce.

By 1893, only 31 people remained at Coranderrk.Pressure from settlers to sell or lease Coranderrk land grew and throughout the 1890s, the Board began to revoke, sell or lease portions of the station.

In 1920, 78 acres were sold to Colin MacKenzie for a fauna research center, now known as Healesville Sanctuary.

Coranderrk was officially closed in 1924, and all but six residents were relocated to Lake Tyers. The remaining families, including Lankie and Annie Manton, Alfred Davis and his wife, Mrs Dunnolly, and Bill Russell, were permitted to stay.

Finally, in 1948, the Coranderrk Lands Bill revoked the reservation of Coranderrk’s remaining land, dividing it for soldier settlement. No Aboriginal soldiers were eligible to receive this land.

For the people of Coranderrk, these events marked the devastating loss of their home and a deep fracture in their community.

Coranderrk Today

Image courtesy of Yoorrook

In 1998 Coranderrk cemetery was handed back to the Wurundjeri people and over the following decade the Wurundjeri acquired a further 119 hectares.

Coranderrk was also added to the Australian National Heritage List on 7 June 2011. The property is now managed by Wandoon Estate Aboriginal Corporation (WEAC).

Coranderrk demonstrates First Peoples resistance to colonisation and the value of their political activism, caring for Country and developing lasting friendships and partnerships.