By Commissioner of the Yoorrook Justice Commission, Distinguished Professor Maggie Walter

This piece was first published by IndigenousX.

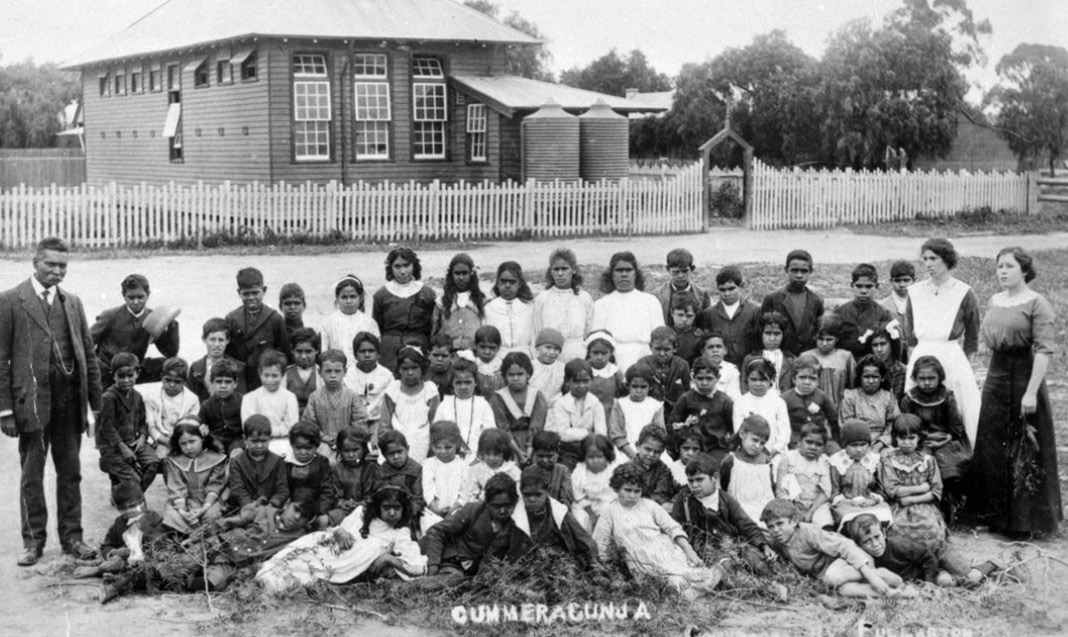

The Yoorrook Justice Commission has been travelling across Victoria as part of its work to put the true history of the state since colonisation on the public record. The Commission has heard from thousands of First Peoples during the truth telling process – the first of its kind in Australia. Commissioner Maggie Walter shares one of the testimonies being presented today, from a First Nations man named Jarvis. Commissioner Walter has shared this with his permission.

Jarvis is telling his story to the Yoorrook Justice Commission, Victoria’s formal truth telling process, as part of its investigation into past and ongoing systemic injustice within the state’s education system.

Jarvis’ evidence will be heard today when the Commission continues its public hearings into health, education, housing and economic life.

Sitting overlooking the waters where the Yarra River and Merri Creek meet, surrounded by soaring gum trees, Jarvis takes a deep breath. With the camera rolling, he begins to tell his story.

Jarvis was about eight-years-old when his all Aboriginal school on the outskirts of Shepparton closed down. He and his cousins transferred to a public school and for the first time it sunk in that he was different, because he started encountering racism,

The racism Jarvis experienced most often wasn’t overt. In some ways it was worse. It was the soft racism of low expectations. Jarvis described it as “passive”.

He said it started with the favouritism of non-Indigenous students.

Jarvis would put his hand up in class and the teacher would go to ten other children before the Aboriginal students. He was regularly made to stay back after school to finish the work he couldn’t complete during the day because he hadn’t been helped.

Some teachers would humiliate Jarvis in front of his classmates if his attention slipped.

“People looked at you like you were dumb,” he said.

“You just have to be walking and you’d feel it…It made it really hard for me to get up and want to go to school, you know, because I knew that it was a fight. It was a fight to get from 9:00 to 3:30 in the day.”

Then in year eight Jarvis was expelled. He retaliated after a teacher had grabbed him around the neck and yelled in his face. “My whole life changed from that day,” he said.

Jarvis never went back to school, and suddenly found himself on a bleak path. He started hanging out with people who were doing the wrong thing, and turned to illicit substances, alcohol and crime. As an adult, he spent years between prison and homelessness.

In his time of greatest need, Jarvis was fortunate to have good people in his life. He would draw on them, and use all his strength to turn his life around. Today he is helping to advance the rights and wellbeing of his people through community engagement work. He wants to do his ancestors proud.

But it shouldn’t have been this way. Everyone wants their kids to have a safe and nurturing school where they can learn and grow. Instead for Jarvis, it was the place that sent his childhood and life spiralling.

Jarvis’ experience at school is not unique.

According to the latest data by the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework, there were three times as many Aboriginal young people aged 20-24 without a year 12 qualification compared to their non-Indigenous peers. The Framework also showed that First Peoples students achieved far lower levels in numeracy and literacy at each year of national testing, and they also felt less connected to their schools. Many indicators such as retention rates from year 10 to 12 are getting worse for Aboriginal young people when they should be getting better.

The impact extends to tertiary education. Just 11 percent of First Peoples over the age of 15 held a bachelor’s degree compared to 29 percent for all Victorians, according to the 2021 Census.

These figures demonstrate a clear failure of the Victorian education system to meet its obligations to First Peoples students. Not only can this failure have a detrimental impact on a young person’s future, but there are broader economic and social implications.

Let me explain.

The median age of First Peoples in Victoria is just 24, meaning that half of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are aged 23 or under. Compare this to the median age of 38 for all Victorians. This largely young population should mean that as the surge of Aboriginal young people move into their prime working years, they will be equipped with the knowledge and skills to have long, fruitful and productive careers. This brings fertile economic years for First Peoples and the wider Victorian economy.

This young skilled worker surge should lead to what’s known by economists as a ‘demographic dividend’. This is an age structure where there is a larger working age population across society that is able to support a smaller dependent population. This benefits everyone.

Yet, the current failure of the education system for First Peoples children means that as this group ages and moves into what should be the prime working years, they potentially will not be able to make the most of them. The demographic dividend is lost, with the costs borne by all, but particularly First Peoples.

What is needed is substantial and immediate investment in primary and secondary school education for First Peoples. It is not too late. The strategies underpinning these investments must be led and controlled by First Peoples. This last part is critical. Yoorrook has heard how the education system has long been failing First Peoples children because it is not designed for them.

Jarvis enjoyed his early primary school years because teachers understood the experiences of Aboriginal children, and students were taught about culture and language. It was run by, and for, community.

Investment into Indigenous children’s education can help transform what it means to go to school for every Aboriginal child in Victoria, so that kids like Jarvis have the same opportunity to thrive as everyone else.