Yoorrook’s social justice hearings wrap up

Victoria’s truth telling commission has finished its social justice hearings, which looked into the systemic injustices faced by First Peoples in education, health, housing and the economy. Read on to find out more about key evidence and moments from the hearings.

The Yoorrook Justice Commission’s social justice hearings ran across more than six weeks and comprised evidence from at least 70 witnesses including First Peoples leaders, experts and community members, Government Ministers, Church groups and university representatives.

Commissioners heard how the violence, discrimination and racism brought by colonisation and perpetuated through ‘protection’ legislation continues today – in our education system, our health system, in housing, in the economy and in the government’s response to family violence.

Scroll down or click a heading below to learn more.

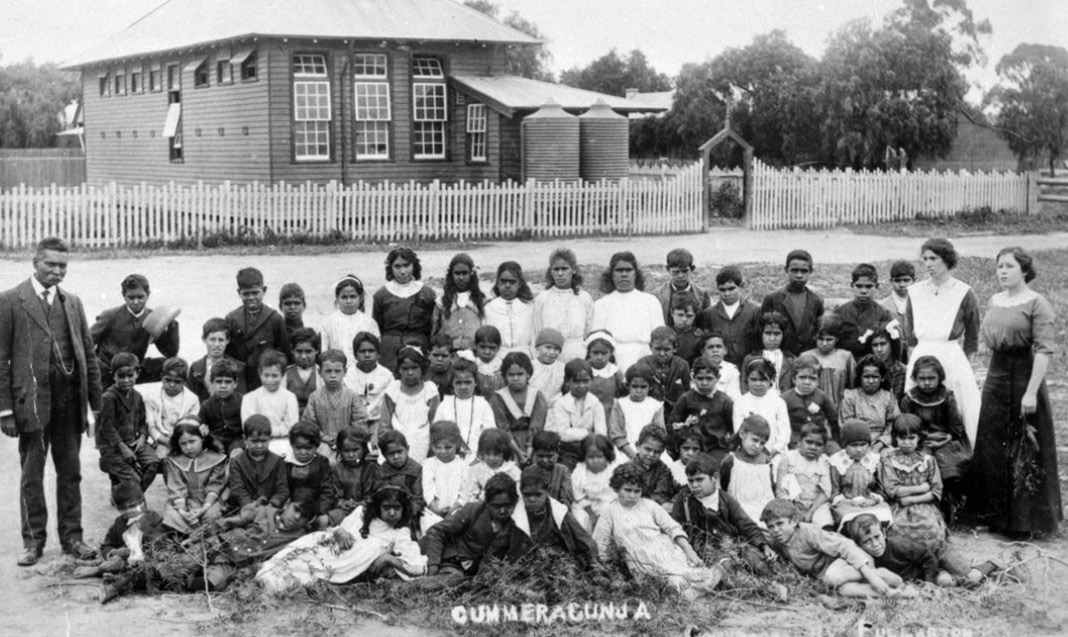

Education

Dr Mati Keynes talked about how Victoria’s curriculum has been a potent and favoured tool of governments to legitimate the settler position as members of the British empire and Commonwealth.

“For more than 100 years in Victoria from at least the 1870s to the 1970s, the curriculum was based on a white settler national master narrative, which was about the benevolent progress of the superior white civilisation here. And it routinely and systematically objectified First Peoples.”

Dr Mati Keynes

Education Minister Ben Carroll said: “Since colonisation schools have played a significant role in reinforcing racist perceptions and stereotypes about First Peoples and perpetuating false narratives about colonial history… These effects can be seen in the racism that continues to be experienced by First Peoples students.”

The Commission heard how health was often used as an excuse to keep Aboriginal kids out of schools. Dr Keynes said it was often weaponised by the local settler families saying First Peoples were unhealthy or had certain diseases or didn’t have shoes.

Aboriginal young person Elias Jarvis spoke about the “incessant gaslighting of low expectations” experienced by Aboriginal students, and how he was made to sit at the front of class so the teacher could keep an eye on him, despite the fact he was an exceptional student.

Health

Commissioners heard extensive evidence of past and ongoing racism and discrimination within Victoria’s health services, both for individuals requiring health care and Aboriginal organisations providing care.

Minister for Health Mary-Anne Thomas accepted that Victoria’s health services are not culturally safe places for First Peoples in this state, and that racism in hospitals was at “crisis” point.

Yoorrook heard countless examples of racism in Victoria’s health services.

“We know that Aboriginal people weren’t allowed into hospitals, being told to wait and be treated outside. Women gave birth on the verandahs, meaning the first experience an Aboriginal baby had was one of racism and exclusion. That’s our lives. That’s how our lives started and continued.”

Aunty Jill Gallagher

Associate Professor Dr Graham Gee, from Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, said: “Not surprisingly racism is not just an emotional violation and devastating, but it’s linked now to a wide range of social health problems, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, stroke.

“It is literally poisonous for your body. And with enough racism it also is linked now to post-traumatic stress disorder, you experience enough discrimination, it filters in and you can experience traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression and what have you. That has been well established now for at least a decade.”

Minister Thomas accepted that the “constant” reporting requirements of Aboriginal organisations was “a continuation of the ongoing surveillance of colonisation, where First Peoples are constantly surveyed as a way of keeping First Peoples controlled”.

Minister Thomas said: “The very best place to deliver the care that First Peoples need and deserve, first and foremost, is through the Aboriginal community-controlled health sector, and continuing to invest in that sector and strengthening that sector is absolutely critical. It is where we will be able to see self-determination in action.”

Housing

Yoorrook heard how today’s housing crisis stems from colonisation. Darren Smith, from Aboriginal Housing Victoria, said “you can draw a line”.

Commissioners were told about how Aboriginal people in Victoria are accessing homelessness services at the highest rates in the country, and it was growing at roughly 10 per cent per year.

The Commission heard that 17 per cent of the Victorian Aboriginal population was accessing homelessness services. Darren Smith said: “If it was in the mainstream there would be 1 million people accessing homelessness services in Victoria every year. It would be an absolute crisis.”

In her evidence, Housing Minister Harriett Shing agreed it was a “crisis”, describing the situation as an “abject failure” by government.

Minister Shing said: “We created Aboriginal homelessness and then we turned away from it. And for too long we refused to even acknowledge that its existence and impact was our doing.”

Family violence

The Commission heard how Aboriginal people have lived within a structure of violence since colonisation, including dozens of massacres in the decades after the Henty’s arrival in Portland in 1834.

Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service chief executive Nerita Waight talked about the mass sexual abuse of Aboriginal women on the frontier, of which police were often “very complicit”. In parts of Australia, the colonialists enslaved and trafficked First Peoples, while the state was directly responsible for causing the Stolen Generations, which the police enforced, she said.

Minister for the Prevention of Family Violence Vicki Ward acknowledged that historically, the systems designed to keep women safe from family violence have been marked by discrimination and systemic racism.

“They have failed to listen to First Peoples women and have failed to keep First Peoples women safe. They have also too often led to the removal of children and perpetuated the intergenerational trauma that child removal can create.”

Minister for the Prevention of Family Violence, Vicki Ward MP

The Commission heard how Aboriginal people have long had to find ways to respond to family violence in the absence of police who don’t attend or care, and government agencies that perpetrate more violence.

VALs said police were dealing with family violence call outs as a ‘roll your eyes’ matter.

Commissioners were told about the compounding risks that come with a lack of safe, stable housing for Aboriginal women and children fleeing family violence, and how this can lead to child removal, disruption to education, or return to an unsafe home.

Djirra said that an Aboriginal woman experiencing family violence in Victoria might stay in a range of temporary accommodations up to eight years while waiting for social housing.

Economic injustice

Commissioners heard how First Peoples have been doing business since time immemorial. Karen Milward from the Kinaway Chamber of Commerce said: “we were trading, we have our trade routes, we set up marketplaces and we trade for things that we needed and that has continued on.”

Yet the Commission was also told how Aboriginal people have been shut out of the economy by a range of barriers including racist legislation, a lack of intergenerational wealth and assumptions that because a person is Aboriginal, they are not educated.

Karen Milward talked about how hard it was for Aboriginal people to get a bank loan because they often don’t have money or assets behind them.

Uncle Paul Briggs said it was difficult for First Peoples “to come back in off the mission” and try to compete in established industries against family run businesses that had been operating for 100 plus years.

Treasurer Tim Pallas acknowledged that all members of Parliament needed to recognise that there is a historical injustice faced by First Peoples that needs to be redressed or righted. He said: “as we enrich First Peoples, we also enrich the State of Victoria more generally.”

Yet the Treasurer also acknowledged that funding was “not adequate” to bring economic prosperity to Aboriginal people within a generation, which was outlined in a framework.

Rueben Berg compared colonisation to a game of monopoly that removed Aboriginal people from their lands so that other people could come and take that land and put up their houses and hotels.

“[Aboriginal people] keep rolling the dice that has us landing on other people’s hotels and having to pay. And, unfortunately, the reality is there’s more ‘go to jail’ spaces for our people as well, and all of these things compound to leave us in this position today.”

Rueben Berg

You can learn more about Yoorrook’s work on our website, including how to tell your truth to the Commission. Follow Yoorrook’s socials to stay up to date on upcoming hearings, events and information sessions.